Editor’s Note: We share travel destinations, products and activities we recommend. If you make a purchase using a link on our site, we may earn a commission.

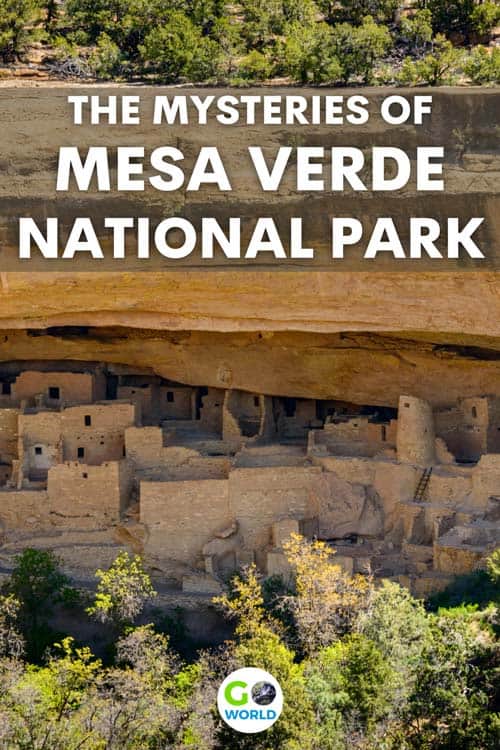

We find the ruins of Mesa Verde National Park frozen in time, much the same as they existed when their Native American denizens abandoned them 1300 years ago.

It’s summer in Colorado. The heat is motionless in the air.

Inescapable dryness and the brutal temperatures of the southwestern United States force us to understand the people who lived in the area, without air conditioning, living off the fat of a very lean land.

My wife and I are staying at the Far View Lodge inside the park’s boundaries, and thankful for the shade. The view from the hotel room expands until the curvature of the earth clips off the silhouettes of mesas at the horizon.

We leave with a national park tour offered by the lodge. Our tour guide, Grant, picks us up and we travel by van with one other attendee further into the park’s boundaries and towards the great ruins.

He’s affable, and almost flabbergasted with excitement at the tour ahead of us, the cultural significance, and the honor of leading it. Both my wife and I like Grant straightaway.

Mesa Verde National Park

We first visit Spruce Tree House, one of the primary dwellings and the one closest to the visitor center, only to find it closed.

It’s currently not available for a tour because the overhanging cliff is suspected to slough off. The danger of a massive rock fall has forced closure of this area pending reinforcement of the above cliffs.

As we take in the vista, Grant explains the “discovery” of the ruins by Richard Wetherill and cowhand Charlie Mason in the 1880’s. They reportedly shimmied down the tree nearest the cliff to access the dwellings, risking life and limb. I would have gone around.

The Wetherill family did great work in promoting the site for protection as a national park, but they didn’t discover anything. In fact, Ute Indian guides informed them of the dwellings’ existence, making the term “discovery” all the more ludicrous.

Grant encourages us to imagine the wonder of that initial viewing. Laying eyes on the site must have been, in his words, a “spiritual experience.”

The secret of the Place

Suddenly being included in the secret of the place must have indeed have been a marvel to those first white settlers. That feeling remains for visitors today. I have a vague sense that I’m trespassing too, as though this place is profoundly not mine.

Ancestral people, or the “Ancient Ones,” occupied the area seasonally as far back as 7,500 BC, but it wasn’t until about 600 AD that they built the first pueblo dwelling on the Mesa, or plateau. This was a major shift. Rather than just hunting and gathering, the natives began to incorporate horticulture into their subsistence.

I can’t imagine anyone farming here. We pass two meager springs, notable only for their surrounding greenery; that greenery soon tapers off back into desert as the water is exhausted or it moves back into underground chasms.

Not exactly a great source of irrigation.

The Three Sisters

Squash, corn and beans – the three sisters – were staples of the people’s diet. These plants are not native to the region. Grant explains that seeds were traded from elsewhere, possibly in exchange for intellectual property.

The Mesa Verdeans were crafty technicians of stone, plant fiber and animal hide. Though renowned for their basket making, the people developed the craft of pottery during the same period that seeds were introduced to the region.

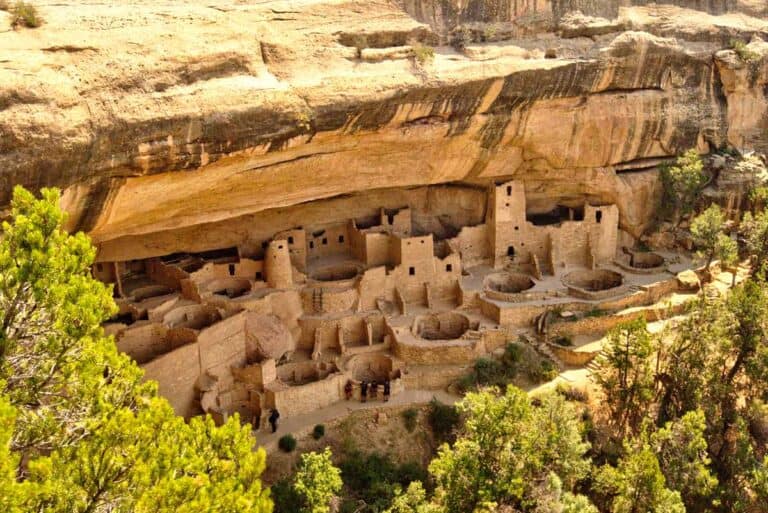

The 12th century marks the beginning of the grand architecture for which Mesa Verde National Park is so well known.

A Brief About the Grand Architecture

The people found that the cliffs protected them from the elements, wild animals and the threat of attack in the event of warfare. If attacked by neighboring tribes, the structure could prevent access because the ladders on the bottom floor of the dwellings could simply be removed.

Similar to European castles, the people could easily defend themselves from above.

The dwellings were a more comfortable living space too. Because they were recessed into the cliff face they provided protection from the south sun inside the cooler stone. The temperature of the rooms built into the cliff can be 10-20 degrees cooler than atop the mesa.

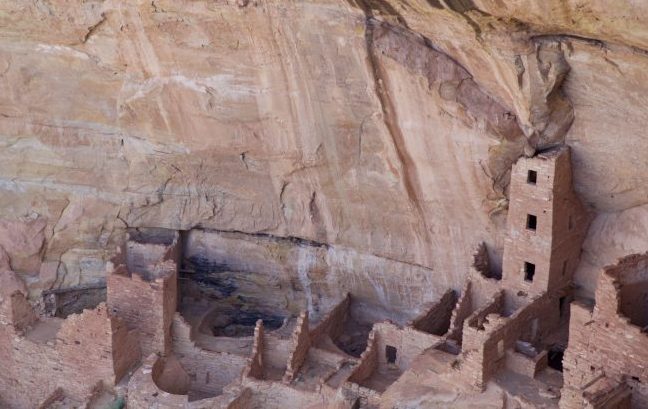

Next, we visit Square Tower House. Grant begins with mention of Navajo Canyon, and as we step out in the viewing area, everyone thinks that its dramatic expanse is the only thing warranting the stop.

It’s a moment before we realize the incredible ruins below and to our right.

Square Tower House

Square Tower House is my favorite ruin because of its central edifice. The blocks are so straight and powerfully upright that the tower completes the rounded, sloping cliff by contrast.

Ancient lichen marks toward the tower make me wonder if it was designed for water collection. No one truly knows the reason for the people’s departure just 100 short years after the major construction efforts that resulted in the cliff dwellings.

A drought occurred during that period, hampering farming, and the social instability that came along with the disrupted food supply may have contributed too.

Some archeologists believe that over population of the community may have left it more vulnerable to the shortages a drought causes. The people fractured into groups that migrated south, eventually becoming the Hopi and Pueblo Indians.

Seeing the Horses

We pass a sign that reads, “Don’t feed the horses.” Grant explains there are indeed feral horses here, and they are indeed dangerous.

Mesa Verde has had trouble with these animals, as well as stray cattle which have trampled some of the ruin sites. All the same, I’d love to see one of these horses up close.

Grant grew up riding horses on the mesa top, searching for relics and avoiding snakes. It’s remarkable that he’s spent his whole life in the area.

His people have history here too, and farmed the area just as the Natives did. When Grant tells us he used to sell bags of pottery shards for twenty five cents, our driver chimes in on the conversation, making note of what is, and what is not, legal.

Fortunately, most of Grant’s “archeological work” happened on private farmland.

Visiting the Cliff Palace

The final site of the tour is Cliff Palace, the mansion of Mesa Verde. The massive 150-room apartment complex is thought to have housed 100 people.

It’s truly impressive, but looking through the roadside telescope makes me want to be down in the action with the guided walk offered by the National Parks Service itself.

Unlike the ghostly barren Spruce Tree House, Cliff Palace is crawling with tourists wearing bright colored clothing that would have been foreign to the ancestral people.

Back at the lodge, we succumb to the heat of the afternoon and only reemerge for a sunset walk. The xeric landscape is fragrant with sage; there are flowers that I can’t identify.

I watch my steps for rattlesnakes, and instead see shiny black beetles. This is a diverse ecosystem that is often unappreciated by those accustomed to thick foliage.

Beautiful Sunset

And the land makes for one hell of a sunset. There’s simply more sky here. Without the tree covering the sky is a wide expanse as grand as the sea. Dusk soon cools the desert.

A black horse appears. It’s far enough away to be a solid black silhouette, but we can tell it’s scruffy. This makes it seem fuzzy, dreamlike, and ghostly. It walks strangely, in uneven steps over uneven terrain. It doesn’t disappear, but rather trots off steadily, anxiously, past a family walking the trail below.

This is a lovely way to end the day, and leaves us wondering about the Native American symbolism of the horse. I don’t look it up on my phone – there’s no cell reception, and no televisions at the lodge for that matter.

It’s refreshing to be disconnected. We wonder and imagine. It’s a fitting way to close the day at a place with more mysteries than answers.

The view from the Far View Lodge, Mesa Verde National Park. Photo by Jack Bohannan

Book This Trip

Ready to see the wonders of Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado? Then start planning by checking out hotel and VRBO options, restaurants on the road, best sights in the park and more on TripAdvisor and Travelocity.

If you’re looking to spend more time exploring Mesa Verde National Park or the surrounding Canyonlands then check out the regional tours offered through TourRadar. Find multi-day trips or just short adventures here.

The best time to visit Mesa Verde is during the summer season when tours are offered more frequently and more ruins are available for tour. A $15 entrance fee applies per car. An annual pass to the United States National Parks can quickly pay for itself, costing just $80 for all parks.

For more information, see visitmesaverde.com

Check out our Colorado Travel Guide for more information on what to do on your trip.

Author Bio: Jack Bohannan is a freelance writer soaking up the sun in Denver, Colorado.

- Discover Claremont, California Along Historic Route 66 - December 6, 2024

- Three Sites to Soothe the Soul in Kyoto, Japan - December 5, 2024

- 13 Essential Tips For Women Traveling in Morocco - December 4, 2024